“‘There was once a strange, small man,’ she said. Her arms were loose but her hands were fists at her side. ‘But there was a word shaker, too.’”

Another week, another war. This time we cross oceans and centuries to find ourselves in Nazi Germany.

The story is a chapter of Liesel Meminger’s life spanning 1939-1943. It is told by Death, who encounters her in the flesh three times before her own demise years later. This qualifies as a young adult novel much more than a children’s book, and it’s kind of cheating because I only read it for the first time two and a half years ago but it deserved a second go.

Read this book.

I could end this entry there because I’m so overwhelmed by what to say about The Book Thief that I just want to skip to my ultimate message. It’s too long (500+ pages) to reduce to a blog entry and I dog-earred what feels like every other page because it has a line or a thought I wanted to share or comment on. So here are some thoughts:

– “They say that war is death’s best friend, but I must offer you a different point of view on that one. To me, war is like the new boss who expects the impossible.” Death makes a great narrator. Subtle reminders of his ever-present nature coupled with a disarming compassion add to the story’s already high levels of tension and heartbreak.

– Few things so plainly demonstrate the complexities of humanity like war; the extremes of bravery and cowardice, kindness and cruelty, impulsive reactions and cold calculations, sitting side-by-side or even battling it out within one person.

– War, despite said complexities, is often depicted in a black and white, good guys vs bad guys kind of way. I think on this side of the world we rarely see stories of German protagonists suffering in World War II. It’s easy to paint the entire nation as complicit in the Nazi regime, while that is clearly not the case. It’s the most clear in cases like Liesel’s adopted father Hans, who refuses to even join the Nazi party despite the dangers of holding out. It’s less clear in cases like Alex Steiner, the father of Liesel’s best friend Rudy, who is afflicted by “contradictory politics.”

– Death can be arbitrary but how you live is not. Hans Hubermann is certainly lucky that young Reinhold Zucker forced him to swap seats on the bus and inadvertently saved his life. He is not, as his sergeant says, “lucky you’re a good man, and generous with the cigarettes.”

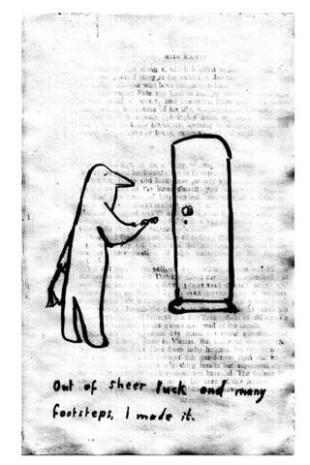

– “She was the book thief without the words. Trust me, though, the words were on their way, and when they arrived, Liesel would hold them in her hands like the clouds, and would wring them out like the rain.” It’s fitting that this kind of eloquent prose litters the pages of a book that is ultimately all about the power of words, in the best and worst possible ways.

– I no longer know what constitutes a happy ending. If you read to the final page, you can make an argument that Liesel’s story ends well, but the chapters before the epilogue make it hard to convince yourself of that fact.

There’s so much more I can say – I haven’t even mentioned Rudy with hair the colour of lemons or Max with hair likes twigs or feathers, both of whom come close to rivaling her papa for Liesel’s love. You should probably just read it yourself though. If you don’t mind some dog-earred pages, I have a copy I’m happy to lend out – just don’t steal it.